As I was reading the Toronto Star recently, I got a horrible scare. The Rothbart Centre for Pain Care, where I had been a patient, was responsible for an outbreak of Staphylococcus aureus (Staph A) in a number of patients. Specifically, anesthesiologist Dr Stephen James – the doctor I had seen, liked and trusted for the year and a half that I was a patient at the clinic, was the one responsible.

Now, this note isn’t about my feels regarding this revelation – for the record, the outbreak happened about a year and a half after I had left their care (I was attempting to get back to see Dr James at that time, but he refused to see me – a blessing in disguise!) Rather, this is about the need for us to be more cautious in our own play, to avoid the dire consequences faced by Dr James’ patients.

Read the articles about the staph outbreak

Public Not Told of Infection Outbreak at Private Toronto Pain Clinic

Pain Clinic Doctor Faces Disciplinary Hearing After Outbreak

About Staphylococcus Aureus (Staph A)

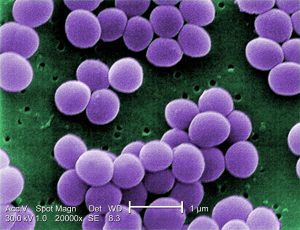

Staph A is a gram-positive coccal bacterium that commonly lives on human skin and in the respiratory tract. While it’s not always pathogenic (producing disease), it is often a source of skin infections, respiratory infections and food poisoning. When that paper cut gets infected? Most likely culprit is the staph already living on your skin – the cut just gave it a pathway into your body.

Over the last few years (more if you work in healthcare), we have been hearing about antibiotic-resistant strains of S. aureus, the most well-known being MRSA (for the love of the Gods, it’s an acronym, so say the letters, don’t try to pronounce it as a word).

Over the last few years (more if you work in healthcare), we have been hearing about antibiotic-resistant strains of S. aureus, the most well-known being MRSA (for the love of the Gods, it’s an acronym, so say the letters, don’t try to pronounce it as a word).

About 20-25% of the population are long-term carriers of S. aureus, except they usually don’t know about it. Staph A is responsible for all sorts of infections, from minor to severe; pimples, boils, cellulitis folliculitis, carbuncles, scalded skin syndrome, abscesses, pneumonia, meningitis, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, bacteremia, and sepsis.

One of the best ways to prevent the spread of Staph A is by simple hand washing.

Breaking the skin during play

As many of you know, I teach many forms of medical play. I am quite thorough in my instruction on basic medical aseptic techniques and the importance of maintaining the sterility of needles that pierce the skin or sounds that enter the urethra. I am also aware that many people feel I am a ‘safety nazi’ or that I am being overly cautious.

Recently there was a thread regarding a needle stick incident, where one respondent said that they used gloves for needle play while in public, but not at home since they were fluid bonded with their partner.

I was blown away – If fluids were the only thing one had to worry about in this sort of play, you could just go and stick whatever rusty, vaguely sharp thing we have laying around the house into our partner without fear of consequences. But we all know the results of that, which is why when there is the possibility that we’ve been stuck with a rusty object, we get off to the doctor to make sure out tetanus shots are up to date.

I was blown away – If fluids were the only thing one had to worry about in this sort of play, you could just go and stick whatever rusty, vaguely sharp thing we have laying around the house into our partner without fear of consequences. But we all know the results of that, which is why when there is the possibility that we’ve been stuck with a rusty object, we get off to the doctor to make sure out tetanus shots are up to date.

Now I’m being a bit facetious there, for sure, but I’m doing it to illustrate a point – When I was suggesting sticking a partner with a rusty nail instead of a sterile needle, you likely thought I was being a bitch – rightly so. Why then, when people suggest using straight pins (inferior metals, can’t be sterilized, often rusty but small enough not to be seen with the naked eye) or bare hands (20-25% of the population carries Staph A, a potentially deadly infection) do people react as if I’m asking them to don hazmat suits each time?

Dr James & the Staph A Outbreak

Toronto Public Health investigated Dr James at the Rothbart Centre. They found that there were deficiencies in his infection control. A total of 9 patients were infected with Staph A over a four-month period in 2012. I don’t want to really guess how many patients he saw over that time, but when I was there, he usually took 20-25 minutes per patient, depending on the procedure – he never rushed.

I will point out that I really liked this doctor, which is rather unusual for me. He was matter of fact but kind, professional and knowledgeable. I was comfortable allowing him to perform painful procedures without the benefit of local anaesthesia (personal reasons). I am saying this so that you understand that my criticisms are not coming from a place of malice or anger.

Somewhere along the way, it is assumed that something (likely the needle, the skin or the stopper in the serum vial) was contaminated by improper touching – touching with bare hands or gloves that have touched a contaminated surface then a disinfected/sterile one.

The presence of Staph A on the skin shouldn’t, in and of itself, be an issue. It’s presence and the presence of other bacteria, fungi and viruses are the reason we wear gloves, use chemicals to disinfect surfaces and skin as well as sterilize instruments and tools where possible.

The Staph outbreak here comes down to human error. When people do things enough times, they often get complacent. Sadly, it seems that Dr James may have fallen into this trap – I hope this is not the case. He will be facing a disciplinary hearing to determine his culpability in the matter but does seem to have taken responsibility for causing the infections.

“I am very remorseful and regretful (about what) happened to these people … I think about it every day that I hurt these people.” Dr James (From Toronto Star)

Toronto Public Health found a number of key things were not done or were done incorrectly at the clinic;

- Surfaces were not cleaned (or improperly cleaned) between patients

- Hand hygiene was ‘sub-optimal’

- Equipment was not properly sterilized

- Surgical masks and gloves were not properly worn (or worn at all – from my experience)

- Vials of medication were not handled in a sterile manner

To add insult to injury, patients were not informed when it became apparent that there was an issue and the clinic is still remaining quiet in regards to getting answers for patients.

What we can learn from this

There are a number of lessons to be learned from this example of serious consequences from minor screw-ups in the medical world. This is a prime example of many of the things that I teach and talk about on a regular basis.

WEAR GLOVES!!

Well, don’t just wear them, learn how to wear them correctly.

Well, don’t just wear them, learn how to wear them correctly.

- Learn how to put them on and take them off properly. (When putting them on, don’t touch too much of the glove, try to only touch the cuff or else you really defeat the purpose. When taking off gloves, remember, glove to glove, skin to skin)

- Learn how to avoid touching contaminated surfaces while wearing gloves.

- Learn how many times you need to change gloves (hint: lots)

- Take a class about medical aseptic (clean) technique. It doesn’t have to be mine, but learn how to do this properly. Make sure you pick your teachers well though (medical backgrounds are probably a good thing to look for)

I am seriously baffled by people teaching piercing (and often other things as well) in less than 2 hours. I struggle to fit the needed information into a 3-hour workshop because most of it is medical aseptic (clean) technique. At least half of the class. It takes time to learn, so take that into account when selecting a class.

The deeper into the body you go, the more serious the consequences when something goes wrong

Part of the reason the consequences were so serious for the patients, in this case, is that Dr James was doing spinal injections.

Now, I know that no one here will be sticking needles into anyone’s spine (please don’t prove me wrong), but I have seen some pretty questionable stuff on FL.

Sticking needles straight into the body, if you’re not trained/licensed to do so is very risky behaviour. I’m not going to get into all the reasons here, but since we are talking about infection we will discuss that aspect of why it’s a bad idea.

Staph A on the surface of the skin, from a regular play piercing, could result in a boil or other easy to clear infection. It may clear on its own or may require topical antibiotics. You may need to visit your doctor for a script, maybe oral antibiotics, you can brush it off as an everyday wound, no big deal.

If you stick a needle straight in, you run the risk of picking up the Staph A from the surface of the skin and transporting it, via the tip of the needle, deep into the body. It can end up in the muscle tissue, breast tissue (mastitis), bone (osteomyelitis, if you happen to nick one or the needle tip rubs one while it’s in), or blood (septicemia).

If you stick a needle straight in, you run the risk of picking up the Staph A from the surface of the skin and transporting it, via the tip of the needle, deep into the body. It can end up in the muscle tissue, breast tissue (mastitis), bone (osteomyelitis, if you happen to nick one or the needle tip rubs one while it’s in), or blood (septicemia).

It should be noted that with the prevalence of community-acquired MRSA on the rise, if you have what appears to be a simple infection – a pimple or boil – that is unusually painful or seems to get worse or has redness that spreads quickly, you need to get to a doctor ASAP. Don’t waste time, go to a walk-in clinic or ambulatory care. As is the case with many things, MRSA is much easier to manage if it is caught early. What was once thought of as a hospital or nursing home only infection is now pretty much everywhere, so learn the signs of infection.

Of course, if we are talking sounds and urethras, then you’re looking at UTI’s, kidney or bladder infections (which can, of course, lead to septicemia if you’re really unlucky, even with proper medical intervention)

In conclusion

I’m really happy when I see people taking things like rope, for example, seriously. There are lots of amazing discussions about nerve impingement due to rope placement, the likelihood of harness hang syndrome, etc. Please don’t think that because I’m not active in the rope community, I don’t follow your progress – I do (just not as intently and with the same passion as some of you do, you guys are truly amazing artists and very dedicated!)

I am, however, very disappointed when things that deserve the same sort of consideration – medical play – doesn’t get it. Is it because the word play is in the description of what we do? It makes it seem light and somehow less dangerous? Or is it because the devastating effects usually aren’t apparent until many years after the fact (Hep C, for example)?

When trained medical professionals can have these serious complications, can make these colossal (yet simple) mistakes, why do we feel that we are so above reproach?

Do you really think that bacteria respect fluid bonding? Do you believe that you are immune to infection because you’ve been piercing without gloves all these years and it’s never happened before?

Want to keep reading?

Textbook of Bacteriology – Staph